Protest and Kant’s Categorical Imperative

By Keith W Faulkner, Ph.D.

I would like to address the May-June 2020 protests here without resorting to the platitudes of “Let’s have the discussion” or “A teachable moment.” Instead of just contributing another opinion, I will address a “meta”-issue, which is what philosophy should really be about. It may seem strange to introduce Kant into the picture given that we have more contemporary voices. But I believe that analyzing the cracks in Kant’s ethics may help us see the nature of protest differently. I will first put aside his Critique of Practical Reason, however, to focus instead on ‘the analytic of the sublime’ in his Critique of Judgment. Then I will shift to Deleuze’s distinction between the cry and discourse.

I was reminded of the Kantian sublime a few days ago while I was watching burning buildings on the news. At the time, I was particularly struck by one of the key requirements for the feeling of sublimity: facing something overwhelming without fear. I then realized then that different people can view the same image with different reactions. If you are a property owner, for example, you will probably feel fear while watching buildings burning. If you are a homeless person, however, you may view the same image without fear. On the reverse side, if you are a protester or someone sympathizing with the protesters, you will probably view the police “show of force” with a great deal of fear. But if you are someone who feels the police are protecting you against the mob, you will not feel fear. In fact, you’d probably feel reassured. I am not talking about good or evil here. I am simply talking about how different symbols of force inspire the feeling of the sublime in different socio-economic groups differently.

So how does this difference affect the Kantian categorical imperative? Kant wrote that the feeling of the sublime is key to feeling what he calls the “feeling of respect” for the law. What he meant by “law” here is not the written rules that govern us, but rather something like the ideal of perfect justice, which cannot be fully formulated. There seems to be a differend between the two groups, each claiming to be acting in the name of duty or justice. This is sometimes depicted as the difference between human rights and property rights, but both these types of rights remain too abstract, too much like slogans, less like actionable plans. The differend in the law here can be analyzed semiotically and concretely by way of the two symbols of the sublime I mentioned above. The question here is: How do these symbols influence how we think?

Put simply, the property owner is not only fearful for his or her own property, but for the symbol of the people’s power, which images of burning buildings convey. A people who had felt powerless before, suddenly see a symbol of their power manifested in protest. (Even Kant, in his time, noted how the French Revolution created a sense of “Enthusiasm” throughout Europe. The “Event,” with a capital “E,” does not just occur in one place, but also in the minds of a people that has not yet realized itself.) This is where the counter-symbol of the police force becomes a perverse kind of hope for those who benefit from the way things are right now. If you are on the protester’s side, you do not feel this as a hope. Not at all! You may ask yourself, “Why the disproportionate reaction to a few buildings burned or a few stores looted?” Because it may become a symbol of the people’s power to disrupt the lives of the powerful. Again, it may be objected by some that “these people are burning their own homes,” but if you are truly homeless or jobless (or on the edge of becoming so), none of this matters! What is important for those who seem to object to destruction is that everyone calls for a “peaceful protest,” which means an ignorable protest that does not threaten the powerful.

It is for these reasons I say there is a crack in the categorical imperative. It assumes a kind of universality of the subject, a kind of commonality of all humankind. It assumes that we can discuss these things and thereby find a solution to our common problems. But it seems as if our discussion only circulates in closed vessels, each on its own side, and not just because we have separate sets of facts, or different ideologies. The division is much deeper: there is no such thing as “the world.”

Why is there no such thing as the world? A few years ago, for example, there was a photo of a dress that some said was gold and others said was blue. We already know that different animals saw things with different colors, but we assumed that all “normal” humans saw things the same. The reason this revelation of difference was so upsetting to some: it put into question the universality of the “subject” of a universal humanity. If we see different colors, it goes without saying, then we may also hear different words or think different thoughts. Then you can no longer assume that someone speaking to you is really saying what you think they are saying.

Why is there no such thing as a subject? It was once thought that the “soul” had to be a simple substance so that it would not dissolve after death. We assume the same thing about our subjectivity today. We also assume that the greater number of subjects who agree as to the meaning or words and things thereby constitute a true and unified world. If the subject fractures, the world does as well. I mention this fracture in the world here only because it pertains to Kant. Kant assumes that there must be a noumenal self, that which says “I think,” for moral autonomy to work. The phenomenal realm is what he called “pathological inclinations.” His categorical imperative works by suppressing these inclinations in favor of a “negative enjoyment” of having one’s will in conformity to the law. This constitutes an antinomy: How can you tell the difference between personal interest or pleasure and the negative enjoyment of duty? You cannot; because there is no such thing as a subject. This leads me back to the protest. Let me dramatize the so-called “subjective” thoughts of both sides:

First, the protester’s viewpoint. I do not want to have to protest racial injustice and police brutality, but I feel called by a higher purpose, a sense of righteousness, to put my own well-being and body at risk in the name of a higher principle. The police are acting out of hatred and racism, which are pathological inclinations masquerading as law. The institutions of justice are themselves pathologically inclined, therefore, I call upon them to live up to a higher standard of universality. I of course couch this in the language of Kantianism to show the structure of universality within this discourse.

Second, the police viewpoint. I am here to fight against the pathological inclinations of the people. They may be calling for justice, but what they are really about is “partying” and taking pleasure in destructiveness. If I do not enforce the rules, then everyone will give in to their pathological inclinations and society will fall apart. When I act violently, therefore, I am not doing so by my own will-power, but as a tool of the silent majority. I am justified in my actions because I represent them. I cannot be held accountable personally because I am just a representative of the legal system. I am just doing my job. Again, Kant’s language.

Now, I propose something radical. Let us ignore this subjective “discourse” structured by the categorical imperative and look instead at the impersonal “cry” or the symbol expressed in the sublime. All talk is just rationalization in a Freudian sense: a way of subjectifying oneself. Each side can justify itself any way it wants. But those subjective justifications do not speak to the real power motivating their actions. (As we know from the law courts, people often act and make up reasons for it afterwards.) The burning buildings, the marches, the cries of the protesters are themselves the symbols of thought, not a reflective thought of subjective judgment, but the pre-reflective of objective determination. The “cry,” as Deleuze puts it, is the thing. The “discourse” is only a kind of secondary rationalization. We make a grave mistake, in my estimation, when we “have the conversation.” Why? Because there is nothing to say in the face of the sublime. It leaves us speechless. We do not have to ask “what they are trying to say,” unless we are operating in bad faith. The cry expresses all that needs to be said. Once again, I restate the reason why dialogue will always fail: there is no such thing as the world. I would rather say, following Deleuze, that it is the cries that make a world. There are as many worlds as there are such expressions. Our only intersubjective world, therefore, is one of expression, not of communication, dialogue, or discourse.

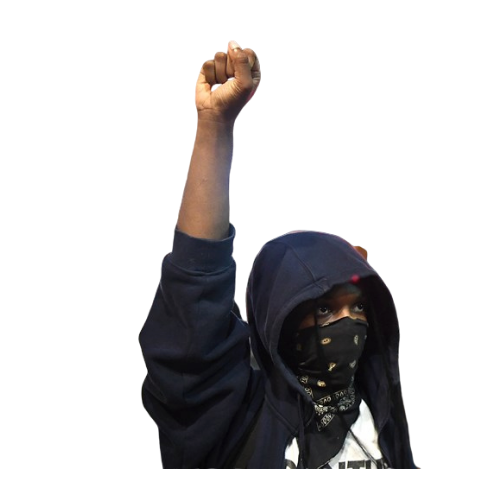

That is why, in this time of protest, I look for the many faces of the sublime. I put aside my own fears, as best as I can, so that I can suppress my pathological inclination to flee, to ignore the cry, or to forget the struggle that no words can capture. I do not want to speak for anyone, even myself, or to understand anyone discursively. Often talking is just a sophisticated way of ignoring what is really happening. The discussion is the trap of Kantian universality or cosmopolitanism. Why a trap? Because when discussion starts, then begins the judgment of how “articulate” the speaker is, how competent the speaker is in the use of language, how speakers make themselves understood in the language of the oppressor. This is the whole point of a minor literature: let the cry express itself outside of the Kantian structure of the law. Being peaceful, under these circumstances, means suppressing the cry in favor of rational discourse. It means that we can “have the conversation.” But because there is no common world to share, we do not hear each other in the same way.

Am I right or am I wrong? That is not a question of expressionism. It is not a question you would ask a work of art. What I am trying to express here is another way of seeing the protest. Take it or leave it, just like you would a painting in an art gallery. By pointing to Kant’s analytic of the sublime, and by hinting at how it could undermine his moral law, I hope to have opened the way to a new understanding of what it means to truly live the problems of philosophy, even in the form of protests, without covering them up with so much needless discourse.

At the same time that these problems are somewhat “meta,” they are also closer to our lived experience than we are even aware, for our conscious mind is clouded by so much talk… talk… talk. If Deleuze has a hatred of discussions, this is part of the reason why. They do not get at the unspeakable problems that make us protest… they do not ask the right questions to make power tremble.

Faulkner Is Associate Professor of Philosophy and the Chair of the Department of Philosophy at the Global Center for Advanced Studies, GCAS College.